As I’ve indicated at several places throughout this website, there is a central assumption at the heart of Evidence Based Medicine which leads to many of the problems with modern research and which, I maintain, explains why EBM doesn’t work in practice. In order to understand this, consider what we do when we want to clincally study a disease or treatment. We start by considering how we can measure the disorder. And in order to measure it, we quantify it. That is,we give the condition and aspects of treatment discrete numerical values.

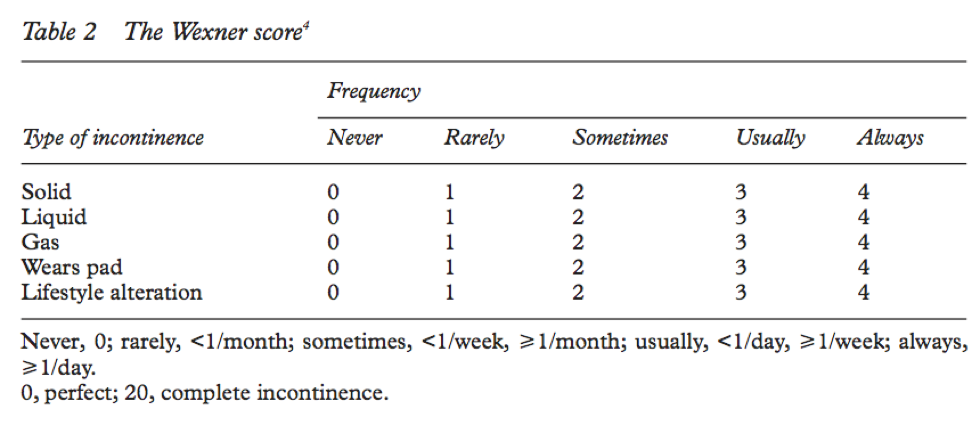

For example, if we want to study the management of fecal incontinence, we have to be able to measure incontinence. Its not enough to say someone’s fecal incontinence is bad or very bad or really terrible. We need to provide an ostensibly objective measure of incontinence which allows us to compare interventions. And in order to do this, we need a tool or instrument which allows us to measure it. Here is an example of one such instrument: the Wexner Incontinence Score.

You can see that it takes a complex phenomena like” fecal incontinence” and breaks it down into its major constituents, allowing us to measure the phenomena. It takes into consideration a number of factors, such as control of gas, liquid, and solid stool, whether the patient needs to wear a pad and how often, and how much it impacts a person’s lifestyle. All very reasonable aspects to consider when assessing the severity of a person’s incontinence. There is a simple calculus which permits us to calculate an incontinence score out of 20. The higher the number, the worse the incontinence. Such scales are exceedingly common and usually undergo evaluation to validate them. The process of validation is meant to assure us that a given tool or instrument measures what it purports to measure. To validate such an instrument or tool is, in effect, to say that it is a correct and true way to measure the phenomena.

Why do we use instruments like the Wexner Incontinence Scale or other instruments? Well, for several reasons.

First, they appear to permit us to measure objectively the severity of a persons incontinence. If I have two patients with fecal incontinence and one has a score of 9 and the other a score of 14, I can reasonably conclude that the second patient has worse incontience than the first patient.

Second, it ostensibly allows us to evaluate and compare different interventions. If I have a patient with a score of 15 and after my advice or treatment he/she has a score of 5, I appear to have improved the incontinence. If a different intervention is used and the improvement is only down to a 10, then it appears the second intervention is not as good.

Third, consonant with the comments above, a scale like the Wexner Incontinence Score appears to provide an objective, reproducible standard or measure that applies across culture and location.

As I mentioned above, there are a great number of such tools and instruments used within clinical medicine and research. Here is a brief list just to prod your thinking on the subject:

- Detsky Modified Cardiac Risk Index

- Ranson’s Criteria

- APACHE II

- Glascow Coma Scale

- Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire

- Crohn’s Disease Activity Index

- Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale

- ASA Classification for anesthetic Risk

- Depression Rating Scale

- Karnofsky Performance Status Scale

- Eastern Cooperative Oncology Groups Functional Index (ECOG)

It should be clear to anyone familiar with medicine that these are but a few of the tens of thousands….no, of the hundreds of thousands of such tools or instruments for quantifying complex medical phenomena. I would defy anyone to recall a clinical study in the past 20 years which does not involve the use of quantitative instruments like the ones listed above. They have become essential to clinical research.

As I mentioned above, these tools or instruments are ways to quantify medical phenomena. Quantification is the process of giving numerical values to qualitative phenomena. Although it is rarely ever discussed as part of the EBM paradigm, all evidence within the EBM paradigm must be quantitative. Every single clinical study in every single medical journal involves quantifying complex qualitative phenomena to allow for measurement. If it is not quantitative, it is simply not evidence. It will never be published, at least not in a reputable evidence-based journal. Whether you wish to study the efficacy of a surgical procedure or risks associated with treatment or treatment of depression, it all has to be measured quantitatively. Indeed, one could summarize by saying that almost all clinical research involves quantitatively measuring phenomena that are inherently qualitative. Consider some of the most common examples: quality of life, degree of morbidity, burden of disease, efficacy of treatment, patient satisfaction, severity of infection, complications of treatment, drug efficacy and safety, response to treatment and quality of care provider-patient interaction.

Now, it is true that some areas of medicine are intrinsically more quantitative than others, such as Pulmonary function tests and lab values. But the vast majority of things we are interested in studying in clinical medicine are inherently qualitative and thus must be quantified in order to be studied within the EBM paradigm. One of the reasons why survival is such a key measure in clinical trials is because it is a relatively simple quantitative measure (e.g., 2 years, 3 months and 15 days). However, as anyone involved with these matters will tell you, survival alone is not a terribly meaningful measure. So we become interested in disease-free survival, burden of disease, quality of life, severity of complications. And suddenly the attempt to measure survival becomes significantly more complicated.

It would be an understatement to say that the quantification of medical phenomena is central to EBM. It is so essential, so primary to the entire enterprise that EBM could not exist without it. The sine qua non of EBM is the quantification of medical phenomena in order to allow for numerical measurements. And because it is so fundamental to EBM, it remains largely invisible, unperceived and unappreciated. “Quantification of Medical Phenomena” is to EBM what the “alphabet” is to writing. It is simply assumed that if you are going to write something then you will use the letters of the alphabet. And so it is with EBM. If you are going to carry out clinical research that is consistent with the practice EBM, such as an RCT, then you will quantify medical phenomena.

Now just to be clear, this is not just my personal view or opinion about Clinical Research. Although most people who do Clinical Medical research may not have given this fact much thought, this is what all experts in clinical medical research will tell you. Medical research is the attempt to measure qualitative phenomena in quantitative terms. Here is a particularly clear description of the process.

Measurement is the assigning of numbers to observations in order to quantify phenomena. In health care, many of these phenomena, such as quality of life, patient adherence, morbidity, and drug efficacy, are abstract concepts known as theoretical constructs. Measurement involves the operationalization of these constructs in defined variables and the development and application of instruments or tests to quantify these variables.

Kinberlin & Winterstein Am J Health-Syst Pharm Vol 65, Dec 1, 2008