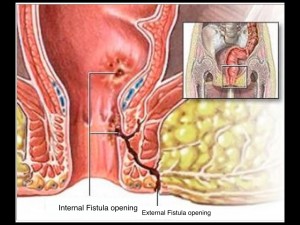

Fistula-in-Ano is a common anorectal disorder, involving an abnormal communication from the anal canal to the skin around the anus. Fistulae around the anus have a storied history, dating back to Hippocrates, who wrote a treatise about it in 400 BC. It is reported that King Louis XIV of France suffered from one and was so bothered by it that he underwent surgery without anesthesia. His surgeon, Felix de Tassy, devised special instruments for the task (shown below) and practiced the procedure on 75 commoners prior to operating on the king. Anyone who knows much about fistula surgery will appreciate the challenge of doing it without anesthetic. The operation was successful and the king was subsequently famous for his toughness and courage. De Tassy received great honours. Incidentally, after his great success on the king, he never operated again. This anecdote may well be the source of two great english expressions: The first one, “quit while you’re ahead”. And second one: “its a royal pain in the ass” .

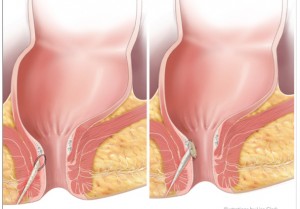

In any event, fistulae around the anus are still extremely common and remain a vexing problem for surgeons because of the risk of injury to the sphincter muscle and subsequent compromise of fecal control. Over the centuries there have been numerous surgical approaches developed for the condition. But none have been perfect and the management of fistulae remains a perennial topic at colorectal meetings the world over. Over the years, surgeons have developed numerous creative techniques for dealing with them and minimizing risk to the sphincter. In 2006, a surgeon named David Armstrong and his group out of Atlanta published a new technique for dealing with fistula-in-ano called the fistula plug. It involved putting a plug made of porcine collagen into the fistula tract. This halted ingress of fecal matter into the fistula tract and functioned as a matrix or scaffolding to permit healing of the fistula tract. Most importantly, it did not involve any damage to the sphincter muscle.

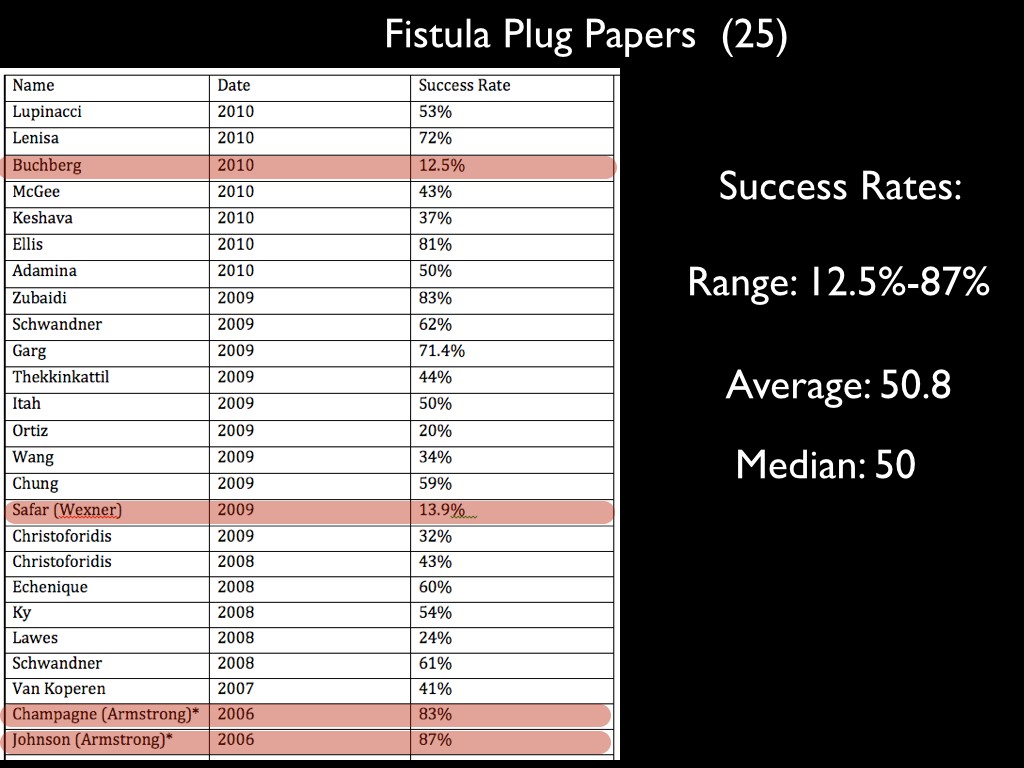

Armstrong’s original results were impressive. I recall watching him present at the American colorectal meeting revealing a cure rate around 85%. He had developed the plug in conjunction with a medical device company and he acknowledged that he held a patent on the plug. Nonetheless, he assured us that it really worked if done properly. His approach seemed to make sense and over the following few years, the technique disseminated widely and was tried by numerous surgeons, myself included. A number of studies were carried out. Here is a summary of 25 of the initial studies which I put together in 2011.

Fistula Plug Results

What I want you to take note of here is that Armstrong’s initial results in 2006 (highlighted at the bottom) show success rates of 83% and 87%. Subsequent studies however, were not as compelling. You can see the numbers vary widely. In fact, the range goes from 12.5-87% with an average of 50.8% and a mean of 50. It would be hard to get better distribution. The Safar (Wexner) study from 2009 had only 13.9% success rate. They comment that the findings in their paper are much lower than previously reported and that “Further analysis is needed to explain significant differences in outcomes”. You can almost hear a trace of sarcasm here.

There have been a number of explanations for the variable results, such as different types of fistula, different surgical techniques, different patient populations, different follow up, overall different study design, etc, etc. But pause and take a moment….. Consider what a range of 12.5% to 87% means? These sorts of variations in medical data tend to just glide of us like water in a shower . We are so accustomed to them, that we hardly take notice of the bizarreness of the results. But stop for a moment and ask yourself what a variation of 700% tells us about this type of research. Where else would you find variations like that. Consider for a moment what it means to tell a patient there is a 12.5% to 87% chance they will be cured. For that matter, consider your financial advisor giving you a range like that with regard to your investments. It is hard to imagine other areas of our lives where we encounter a variations of 700% and tolerate them, except perhaps when it comes to certain corporate accounting practices (i.e., Enron, Nortel). Now we could debate these matters at great length, but I would suggest, as I did before, that you whether its possible, just possible, that the vast discrepancies in these findings are not simply a result of the differences in the way the research was carried out ( ie. whether surgical techniques differed or types of fistula or patient populations) , but rather whether its possible that these results are due to something much more fundamental within the methodology of EBM? Is it possible that there is a confounding factor at the heart of the methodology and which leads to such disparate outcomes?