OK. So we’ve established that quantification is the central support of the Evidence-based Medicine enterprise. And that it is the sine qua non of EBM. So what? What’s wrong with quantification? What’s it got to do with anything, you may ask?

Well, nothing really. So long as you constantly remember that quantification is not a true representation of the phenomena. And as long as you remember that in the vast majority of cases it is, in fact, a very primitive representation of the phenomena. Quantifying a patient’s pain on a scale of 1-10 may be very useful for a nurse who is trying to see whether the analgesic he/she administered an hour ago helped. But it is not an objective standard that transcends time and culture and individual experience. We often forget that pain is not a scale, but rather an experience.

We have become so accustomed to quantifying subjective qualitative phenomena, that we have forgotten that quantification is a proxy, and in the vast majority of cases, a very crude proxy of the phenomena we are observing.

When you fill out a questionnaire or survey, say assessing your experience with a product or service, do you ever have the feeling that the answers just don’t correspond to your experience, that the options provided don’t really match your thoughts or feelings? That feeling you have of uneasiness, of dissatisfaction is a reflection of the artificiality of the quantitative tool. It is generated by the fact that the questionnaire is shoe-horning your responses into a predetermined matrix of discrete possible answers, many of which may not match your actual feelings or thoughts at all.

Let me give you a practical example to illustrate this. Consider what you might say if you were asked to evaluate a meal at a restaurant. You might provide a qualitative narrative about your experience and say the following.

It is a quaint restaurant with a warm, cozy ambiance. The server was friendly and efficient. The soup I ordered was not terribly hot, but that was quickly remedied when I mentioned it. It was otherwise very tasty. The main course, a Thai Green Curry, was somewhat spicier than I expected, but very flavourful and came in a generous portion. The rice was a little over-cooked, in my opinion. Desert was delicious and the decaf espresso was excellent. Price-wise, it was not cheap, but well-worth it. The chef came out and greeted me personally.

Now, imagine you were asked to evaluate the same meal using this quantitative questionnaire using a scale of 1-10.

No doubt you see what I am getting at. Your quantitative evaluation is a far cry from your qualitative narrative.

It is true that people might be interested in your quantitative evaluation or in the aggregate numerical data provided by many people who rate the restaurant according to the questionnaire, but we should not confuse those numbers on a scale of 1-10 with the ambiance of the restaurant, the smile on the waiter and the great coffee.

The effects of quantifying medical phenomena are profound. Quantification is like a cattle chute which forces a widely spread herd of cattle into a single row animals for easy processing. It forces an artificial structure onto amorphous phenomena.

The process of quantification in clinical research over-simplifies complex medical phenomena. And not infrequently, it distorts and misrepresents it as well. It creates a facade, a veneer of objectivity and false sense of confidence, while glossing over the inherent subjectivity of almost all clinical research. The quantification of complex phenomena like quality of life or burden of disease may occasionally be useful when trying to get a ball-park sense of how a patient is doing, but it does not come close to doing justice to the phenomena at hand.

When you pull aside the curtain of EBM, it is clear that it is nowhere near as objective as it purports to be. The process of quantifying complex medical phenomena is a false God and it has distorted and contaminated almost every aspect of clinical research. Just because we give complex phenomenon like faecal incontinence a fancy numerical value does not make it objective.

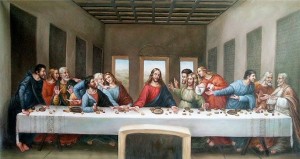

In fact, in most cases it is utter nonsense. It is like quantifying “connectedness” and “fulfillment in life” . And that is why we so frequently get anomalous and peculiar results. Attempts to quantify severity of illness, burden of disease, degree of disability, severity of complications, extent of depression, quality of life or experience, response to treatment, surgical technique are fraught with uncertainty and inexactness. Quantification in Clinical research may give us a vague outline of the phenomena, but it does not come close to reproducing the original. In many cases it is a crude and inexact as trying to measure the thickness of a piece of paper with a ruler.

So this is what I mean when I refer to the underlying misconception at the heart of EBM. EBM is premised on a notion of quantitative evidence… that is, numerical evidence which objectively measures the medical phenomena we are trying to evaluate. And the truth of the matter is that this approach to medical disease profoundly distorts and misrepresents medical phenomena. It is what I call the “fallacy of quantification”.

When you really think about it, at its heart, EBM is a narrative of what constitutes good evidence. That is what the hierarchy of evidence is all about. But it presumes that all evidence must be quantitative. There is never any discussion of this. Qualitative evidence is never even considered. As I said above, there is nothing really bad about the process of quantification, as long as you constantly remember that it is an inexact, primitive substitute for the real phenomena. As long as you remember that in most cases, the process of quantification cuts up the phenomena with the same fineness that a chainsaw slices a strawberry.